Welcome

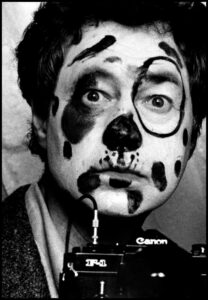

Elliott Erwitt's self-portrait, San Francisco

1979

Welcome

Welcome to the Elliott Erwitt exhibition, brought to you Tempora, in partnership with Magnum Photos. As you move through the exhibition you will firstly discover his personal work, always photographed in black and white. You will then be immersed into the world of his colours and his commissioned works.

Elliott Erwitt is not very talkative about his photographs and the meaning of his work. But you will hear from him nonetheless.

EE : “In general, I don’t think too much. When I talk about my pictures, I have to think a little bit, and I’m honest but I don’t know what’s really from me or what I have heard from someone else or just where the words are coming from.”

This voice is not that of Elliott Erwitt but that of an actor who has lent his voice to his. This voice, which you will often hear, is an exact reproduction of what Elliott Erwitt said or wrote. You will have no other perspective than his, and yours. For my part, I will provide you with information on the context in which his photographs were taken all around the world.

We wish you a surprising visit through the lens of Elliott Erwitt.

Californian wing-mirror

Berkeley, California, USA,

1956

Californian wing-mirror

This photograph has become one of the icons of Elliott Erwitt’s work. Two faces in love, with sharpness of focus, against the blurred beauty of a setting sun over the Pacific. It conjures up countless references from the history of art and photography. It has since generated others.

EE : “This picture was not set up, I knew the people in the photograph, but they were not set up. They were just knocking in their car and I was nearby”

It’s a snapshot.

Taken in 1955 on a California beach for Life magazine, the photograph was published in an issue devoted to romance. It sits alongside other photographs that paint a romantic picture of the stages of love, from the beginnings of a relationship to a wedding anniversary that spans decades. At the time, this photograph did not attract much attention, neither from the photographer, nor from publishers or readers. In 1988, while conducting an in-depth classification of his photographs, Elliott Erwitt rediscovered the photograph. After several decades of silence in the archives of Life magazine and in the photographer’s drawers, it became the ideal photograph, perhaps the best known to this day. The way we view photographs may change, but the way we view the perfect shot endures.

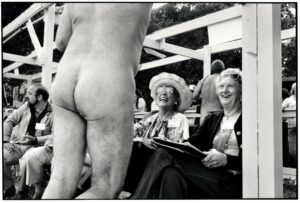

Nudists

San Bernardino, California, USA,

1983

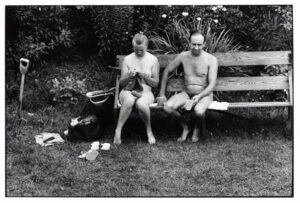

Nudists

Elliott Erwitt was interested in nudism since the 1960s. He produced several articles on nudist colonies in the United States and Europe.

EE : “Nudist colonies are ideal for photographers«

Their way of living in the nude and especially of dealing with people in clothes or having to wear indispensable accessories such as shoes, amused him greatly.

The photograph of this peaceful couple sitting on a bench, the lady knitting and the gentleman finishing his tea, dates back to those early adventures.

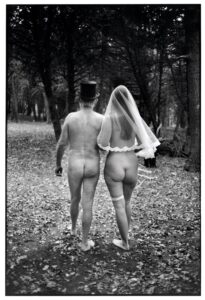

In 1983, he made a personal documentary film Good Nudes on the subject, from which the other two photographs shown here are taken. One is set in England.

EE : “I cannot imagine anybody being funnier than the English nudists”.

This scene takes place at a wedding where the bride is accompanied by her father to the ceremony.

The other takes place in the United States during a Miss and Mrs Nude Competition in California.

EE : “What could be more comical than a small group of average Americans practicing nudism. And then, when those same American nudists are competing in a beauty contest, with a fully clothed jury, you have a story. One of the contestants is trying to influence the judges’ verdict… he lost”.

For Erwitt, you just had to get the right angle at the right moment.

Kent, England, 1984

Kent, England, 1968

Family portrait

Shreveport, Louisiana, USA,

1962

Family portrait

Elliott Erwitt began his career taking photographs of people in his family circle, but also his neighbours, his dentist; everything was of interest. Spotted by Robert Capa and George Rodger as a brilliant purveyor of intimacy, he joined Magnum in 1954 as a family photographer. One might imagine that this is a shot taken at a family party. In fact, it is the result of a commission for an American life insurance company. The company offered a family portrait by Elliott Erwitt as part of the subscription. A brilliant sales idea, which in addition to its originality, still offers us an invaluable portrait of one aspect of American society in the 1960s. Here we see how Elliott Erwitt adds his personal touch to fulfil sales orders.

Soviet wedding

Bratsk, Siberia, USSR,

1967

Soviet wedding

On several occasions, Elliott Erwitt travelled to the USSR for American and European magazines. In 1967, he had the opportunity to travel as far as Siberia. There he photographed the daily life of the inhabitants, providing a new vision of Soviet society. He visited a place where weddings were held. Among the prints, this one questions the reality of the couple’s happy union. It’s an unexpected moment, unsettling, the shared glances that leave the viewer wondering. Elliott Erwitt confided several years later:

EE: “This is a picture I give to any of my friends who get married or divorced”.

He says ironically of himself that all his marriages lasted 7 years.

Paris Trocadero

Eiffel Tower 100th anniversary, Paris, France,

1989

Paris Trocadero

In 1989, Elliott Erwitt was in Paris. There he took one of his most famous photographs. A couple embracing, confronted by the wind and the unexpected arrival of another airborne individual. All this against the backdrop of the famous and celebrated Eiffel Tower – if you look closer, you will see that its great age, 100 years, is inscribed on the metal. This scene seems natural, candid and self-explanatory. On closer inspection, it is not. Since when do passers-by enjoy such a beautiful embrace, in bad weather, armed with umbrellas? It is in fact a carefully prepared and constructed photograph: the reflections are precise, the man jumping is a professional choreographer, the embracing couple fighting against the wind are actors. Other figures have been placed in the background on the right to match the sculptures of the Trocadero. However, this admission does not detract from the absolute magic of the image.

EE : “This picture was an illustration for something – I forgot what – but it’s turned out to be a very popular photograph, that has a second, and third and fourth life like many pictures that are taken by my colleagues at Magnum who retain copyrights of their photographs and by virtue of owning them can sell them again and again to various clients”.

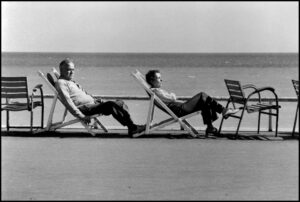

Deckchair sequences

Cannes, France,

1975

Deckchair sequences

Roy Stryker, director of the Oïl Standard project, who gave Elliott Erwitt his very first commissions in 1953, always wanted there to be a story. Even then, Elliott Erwitt firmly rejected this idea.

EE : “To this day, I’m not really sure I know what a picture story is, because a story is not what a photographer does. A story is an editor’s concept. I could go out and make him some nice pictures, but it was up to him to structure the story.”

On the other hand, Elliott Erwitt had a real passion for cinema to the point of concieving and producing several films as personal projects. From this combined passion, he developed a very distinctive practice: sequences or “photo toons”, a kind of intermediary between simple photos and films.

Marshall Brickman, a screenwriter who has worked on several Woody Allen films, writes: « We directors need thousands of images, 24 per second to tell a story. Elliott reduced that to two or three at most.” Marshall goes on to comment on Elliott’s sequence: « Frame number one: a couple is sitting on two canvas deck chairs. Frame number two: the couple has left and the canvases are billowing. The missing frame, the one we imagine ourselves: an image of the wind blowing them out of the chairs and the frame, perhaps onto the pier, perhaps to the moon. As with all good jokes, we complete the thought with the missing piece and the laughter that goes with it by being aware of the idea and recognising the shared moment.”

Having observed him shooting one of these sequences in New York, Marshall Brickman sees Erwitt as ‘a first-class pickpocket’.

Take a moment to look at the other photo toons in the exhibition, and imagine the rest of the story!

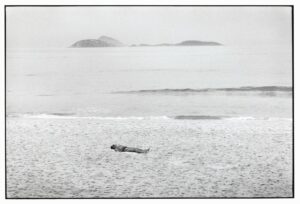

Exotic beaches

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil,

1986

Exotic beaches

Although Elliott Erwitt was more inspired by urban scenes, beaches gave him the opportunity to photograph nature. For Erwitt, a landscape is a place where humans are welcome. The presence of an individual, however discrete in the frame, seems to enhance nature, which returns the compliment.

EE : “I’m not interested in landscape. Just people. I like plastic flowers…

I spent some time in Brazil it is a very good place to take pictures, very colourful, very human”

His point of view remains on the beach. He observes, describes and carefully captures the way in which Brazilian women approach the sea: walking to the water with a firm step, waiting for two waves to splash them and then returning to the beach. He also comments on their beach survival kit containing powder compacts, long-toothed combs, dark glasses, lipstick to match the bikini of the day, hairclips, and enough money to buy a coffee.

Just a diligent and thorough observation of what’s going on as seen through his lens.

Bùzios, Brésil, 1990

European beaches

Brighton, England,

1956

European beaches

Elliott Erwitt grew up in Italy, and for ten years he spent a month’s holiday on the beaches of the peninsula. This childhood experience was carried through into his adult photographic practice, making the beach a natural place for him.

In this series, conceived in England in the 1950s, he captures a particular relationship between man and the sea, a completely different way of experiencing the beach:

EE : « The only reason the English go to the beach is to make it their own. Dressed in their best clothes, they fight it out, mark out their territory, get out their white bean and tomato sauce sandwiches, or whatever it is, and then they sit down. They play a sport they call ‘dipping’: you roll up your trouser legs about four inches and put your feet in the water; then you stand still, in communion with nature (or if you’re in Brighton, staring warily at France). »

In this second photograph, another of Erwitt’s favourite themes appears: children. These children, on the fence that separates the beaches, are pushing the limits of their freedom.

Valencia, Spain, 1952

New-York

Central Park, New York City, USA,

2011

New-York

Born in Paris and raised in Italy, Elliott Erwitt left war-torn Europe for New York on September 1, 1939, as a stroke of good fortune. He then went to California for a few years before settling permanently in New York in the 1950s.

EE : “My first impression of New York was in 1939 when I emigrated to this country and landed in New York and it was a wonderful impression which continues. New York is a wonderful place, this is where I live, this is… what I identify with and New York is the centre of my life, my activities, my family.”

He produced hundreds of images of the city and its buildings. Here, Elliott Erwitt offers us his black and white vision of New York’s Central Park over four seasons, taken from his flat, a colourful souvenir from our schoolbooks.

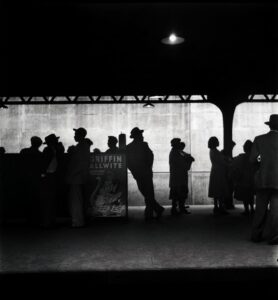

New-York Street

New York City, USA,

1948

New-York Street

Erwitt would also take an interest in the lives of all of New York’s inhabitants, becoming a famous street photographer. New York was then the most cosmopolitan city in the world and the photographs he took there soon entered the political arena, in particular in support of the black community. These men and women, whose silhouettes are accentuated by the backlight, are grouped around an advertisement extolling the virtues of a whitening product.

Moscow missiles

Parade in Red Square for the 40th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, Moscow, USSR,

1957

Moscow missiles

In 1957, Elliott Erwitt the photojournalist went to the USSR for the magazine Holidays. He stayed there for a month to document the development of satellites, the Soviet winter games and its athletes, a community farm and the 40th anniversary of the October revolution. He found himself invited to Red Square.

EE : « I had a pass to see the parade, but I didn’t went where I was supposed to. Instead I attached myself to a Soviet TV crew and walked with them through five security lines. (…) The parade is one of incredible precision, most impressive.

He discreetly captured the crowd and the military parade. And the new Soviet missiles.

EE : “I shot three or four quick rolls and then raced to my hotel room a few blocks away, where I processed it in the bathroom. Unexposed film is suspicious-looking and I didn’t want to risk them X-raying it. Besides, negatives are easier to hide.”

These are the very first photographs in the West of those frightening weapons, foiling the American strategy. Elliott Erwitt recounts that, realising immediately the importance of his photographs, he warned the New York office of Magnum by telex that « there is something very important here. ». Then he hopped on a plane to Copenhagen to get them out of the USSR and prevent them from being confiscated. They were published on November 18 in the USA. These images propelled Elliott Erwitt to the status of a reporter for international, political and strategic issues. He worked regularly for Life, Newsweek, Holidays, Look, Fortune, Saturday Evening Post and The New York Times.

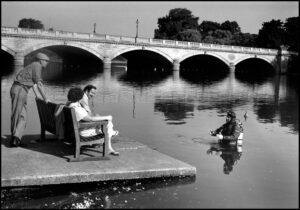

London Paris

Paris, France,

1952

London Paris

Erwitt’s work celebrates Paris, the city where he was born and grew up, spending another year there when he was ten. He returned there very often, photographing the architectural beauty and the private lives of its inhabitants.

His favourite Parisian themes are passers-by, lovers, museum visitors, dogs and café waiters. With a sense of humour, he constantly pokes fun at its inhabitants.

EE : “Paris is the city where I was born. It is a beautiful, beautiful city. It’s got a lot of French people in it, which is one of the disadvantages of Paris. But it’s beautiful and I go there all the time. It’s a special place.”

In this shot of a Parisian crossroads, Elliott Erwitt would no doubt have been amused to see the woman with the umbrella walking across without using the pedestrian crossings, and the young man on the right preparing to do the same.

London, England, 1978

London, England, 1978

For Elliott Erwitt, Paris is just one step away from London.

EE : “I think London is a very “picturesque” city. In fact, I think I went to London more frequently than I went downtown while living in New York, and as I always have my camera, and as London is a particularly picture-worthy place, I took a lot of pictures.”

These two images confirm his words. We are amazed by the lack of surprise of the police officers, who are grouped together in front of this strange car, or by the improbable dialogue with a diver whose hands seem to be indicating the size of a fish found in the waters of the Thames.

Between cities

Wyoming, USA,

1954

Between cities

To photograph cities, you have to get from one to the other. In 1954, Elliott Erwitt undertook a grand tour of the United States where he took a series of photographs without ever getting out of his car. This led to some comical situations. The photos are taken at the speed of travel. On this winter road in Wyoming, one has the impression of a frantic race with the train running at full steam. In the print, Erwitt keeps the edges of the rear window at the top and bottom of the picture. In the other picture, our gaze turns with the steering wheel whether we want it to or not, even if we remain still.

Indianapolis, Indiana, USA, 1953

Another journey, another time and the incessant humour of Elliott Erwitt. No doubt this woman, in the telephone booth of this Irish village, will have to wait a while before getting her call through.

Shanagarry, Ireland, 1982

Architecture

The National Congress building by Oscar Niemeyer, Brasilia, Brazil,

1961

Architecture

Elliott Erwitt was interested in cities and the architecture of buildings, often the most modern ones. He went to Brasilia in 1961, where he had the opportunity to photograph a city that had been entirely conceived with modernity in mind and had just been built. He was aware of the difficulty of photographing such buildings and yet he wanted to highlight them, which their environment did not always allow. In the midst of this gigantism, the frail and central silhouette of the man provides the sense of scale.

EE : “You have to get up early to see it in the morning light; you have to navigate around it, figuring out its best angles, its worst; there are even times when you have to figure out a way to flatter it a little. It’s much more subtle, and I guess much more dull, than other kinds of work – I mean, you can’t get a building to giggle or compose itself. Taking pictures of architecture is a lot like taking picture of sculpture or still-life, only you can’t move it. Here you can make it move by finding the angle and finding out where the sun will be.”

The confrontation between these two photographs is unexpected: an overwhelming orderliness in Brazil, a joyful disorder of clotheslines displaying a thousand items of clothing testifying to life in this district of New Jersey.

Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 1954

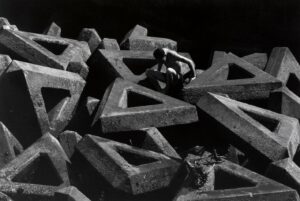

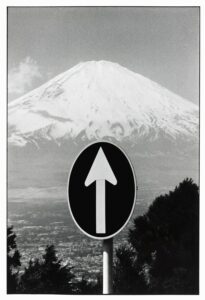

Japanese jumble

Enoshima Island, Japan,

1977

Japanese jumble

These two photographs taken in Japan recall the photographer’s connection with the Nippon archipelago. He went there for the first time in 1958, on his own initiative, and brought back a series of images of Tokyo and Hiroshima. Erwitt wanted to communicate to the world the importance and absurdity of the nuclear tragedy. Magnum distributed these photographs to several publishers, but they were never published so as not to tarnish America’s image.

The present image, taken in 1977, echoes this story. It must be a dike or embankment of some sort, but it appears here as a tangled pile of concrete with aggressive triangles from which humans are trying to extract themselves in order to get back on their feet, a tangle that they themselves have made.

In the same year, Erwitt made a documentary film about the Japanese tradition of climbing Mount Fuji, from which the other photograph is taken. In this film, humanity is present in the form of a fragile city at the foot of the majestic volcano, whose vertical spire appears to show us the direction to follow. Elliott Erwitt made numerous trips to Japan.

Mount Fuji, Japan, 1977

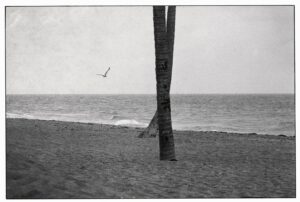

Seagull abstraction

Coney Island, New York City, USA,

1975

Seagull abstraction

Seagulls are often present in Erwitt’s work, particularly in this section, as if their unruliness and silhouette invite them into photographs that tend towards abstraction.

EE : “I had to wait a long time for this one, this is in Coney Island, which is a flyway for airplanes, so the problem was to wait until the airplane was in the right spot and the seagull was looking in the right direction, so I was there for a long time (laugh) finally… luck is so important in photography ! Luck and this sort of instinct.”

EE : “For years I tried to take a particularly spectacular photograph of seagulls, but I never succeeded. You never know for sure which direction they will take, or whether their wings will be half-folded or fully spread. You can include them in a great scene, but you can’t rely on them.”

Daytona Beach, Florida, USA, 1975

Motels abstraction

Motel Room, Texas, USA,

1962

Motels abstraction

Erwitt also explores abstraction through the man whose presence, in the following two photos, is expressed by his absence. The television set, like the armchair, underlines this absence.EE : “I love motels, especially those with a broken double screen door and lino that rises slightly at the corners.”

The photograph of the armchair is from a feature on bad taste published in the United States in 1962. It is a room in a luxury hotel in Miami Beach. This black and white print does not erase the effect of the coldness of the room, which we imagine to be shiny, pink and immense in its full-colour version.

Miami Beach, Florida, USA, 1962

Thoughtful women

USA. New York City.

1955

Thoughtful women

With its pensive woman, bar stool, empty Formica counter, sky seat and cold light, this photograph is a nod to another American master of composition, Edward Hopper. It also bears the hallmark of Erwitt’s great photographs: structured around diagonal lines, it features a vast range of tones from white to black, and multiple reflections.

Elliott Erwitt was able to capture the everyday lives of many women, often those around him, but also strangers, like this woman asleep in a waiting room. Although we don’t have much information about these two images, they are nonetheless inspiring in the way he creates a work of art from a scene of everyday life.

Fernandina Beach, Florida, USA, 1950

Jackie Kennedy

Jackie Kennedy, Arlington, Virginia, USA,

1963

Jackie Kennedy

E.E. « The photo you see here was taken at Arlington Cemetery on the occasion of the funeral of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who had been assassinated a few days earlier in Dallas, Texas. The grieving widow is, of course, Jacqueline Kennedy. At the time, I was in New York and accredited to the White House, so when the event happened, I rushed into town to cover the ceremonies that followed the assassination, in Washington and in Arlington, where the President was finally buried ».

With regards to this photo, he explains his position:

EE : « I’ve developed a technique that’s been very successful: after following the crowd for a while, I then make a 180° turn in the opposite direction. This has always worked very well. But then again, I’m very lucky ».

Thanks to this unique position, he captures pain and dignity. He then discovered, during the development of the photograph in the darkroom, that a tear had fallen onto the black fabric.

Robert Capa

Robert Capa's mother, Julia, Armonk, New York, USA,

1954

Robert Capa

In this photo, a mother kneels in a gesture that looks like a final attempt to protect the life of a son who died too soon, an expression of irreversible separation.

It is the mother of Robert Capa, one of the founders of Magnum. Robert Capa is not his real name. It was another beloved woman, the photographer Gerda Taro, who invented this easy-to-pronounce name, allowing him to remain anonymous for some time and even to create the myth of a brilliant American photographer. The stone also bears the inscription « Born in Budapest », a reminder of his flight from the advance of fascism in Europe. He left Hungary in 1931, when he was just 17, because of the political situation. He went first to Berlin, then to Paris and finally to New York. Robert Capa covered many conflicts, including the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War and finally the Indochina War, which took his life in 1954. The word Peace (Shalom) is written in Hebrew on the last line of his tombstone.

EE : « Julia Capa was a friend of mine. I used to drive her to Armonk to visit her son’s grave. Everyone at Magnum was devastated by the death of Robert Capa and, a few days later, by the death of Werner Bischof and, a few months later, of David Seymour. It is a miracle that the new Magnum agency did not collapse as a result. But the agency has survived as a kind of testament to the sense of mission and energy of the remaining members, whose guiding principle was a particular humanist vision of the world through photography – and the protection of our copyright ».

Grace Kelly

Grace Kelly, New York, USA,

1955

Grace Kelly

This is a magnificently composed photograph: in the foreground, two men with their backs to the camera focus on an elegant, radiant woman, Grace Kelly. This photograph was taken at a momentous event in the 1950s: Grace Kelly’s engagement to Prince Rainier of Monaco, marking the union of a film muse and a prince; all the ingredients of a glamorous tale between worlds discreetly frequented by Elliott Erwitt:

EE : « I went to this event without the proper equipment, I didn’t have a flash and it was quite dark. I was relying on Life magazine’s flash, which worked erratically. So what I did was simply take a chance, open my shutter, hope the flash exposed my film, close the shutter, then continue the process. This photo is one of my lucky shots with their flash ».

Woman with watermelons

Managua, Nicaragua,

1957

Woman with watermelons

EE: “This photo was taken in Managua, Nicaragua. I was there on assignment for Fortune magazine. I have to say that this photo was not part of the assignment. But when you travel to a foreign country, you see things! And as I always have my camera with me, I took this photo. Fortunately, I was able to take it at just the right moment, as it was the 36th and last image on my film. One of the problems with conventional film cameras is that, unlike digital cameras, they only allow a limited number of shots. So you have to be vigilant and if you find yourself in a situation that can change, you have to take into account the amount of film you have left and the number of shots remaining, because you risk missing the critical moment if you’re not careful« .

Empire State

New York, USA,

1955

Empire State

For this other photo of a woman with a distant gaze, Elliott Erwitt recounts how he went up to the top of a skyscraper on a visit and spotted this woman, a tourist admiring the view of the Empire State Building. It’s a snapshot, then, in which we find the horizontal and vertical lines so dear to Elliott Erwitt and which are often seen in his architectural photographs. Note the importance given to the woman in the foreground. The sharpness and contrast allow her to stand out perfectly against the hazy New York background.

Woman child cat

New York City, USA,

1953

Woman child cat

EE : “This is a picture of my first wife, first child and first cat”.

Women, children and animals are three of Erwitt’s favourite subjects. Here he offers us three lives connected by a look of amazement and wonder, a scene that is both intimate and universal. The photographer says he prefers black and white because it favours synthesis, and this is an obvious example. The mother and child are gazing at each other tenderly under the watchful eye of Brutus, the cat rescued from the street.

Taken in New York in 1953, this photograph was one of the highlights of the exhibition « The Family of Man » at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1955, in which more than 500 photographs from 68 countries were exhibited.

EE : “it [this picture] has been used consistently over the years. You could say that it put one of my kids to college.”.

Child’s shattered eye

Walden, Colorado, USA,

1955

Child’s shattered eye

EE : “It’s just a kid I saw in the school bus in Colorado. Essentially the picture was there, and I moved very little in order to strengthen the juxtaposition.”

In 1955, Elliott Erwitt won a competition called Baby-Boomers which aimed to photograph children born in 1945 all over the world. Erwitt was in charge of the American section. He was asked to show a happy American heartland, illustrated by a family living on a ranch. Elliott went on the road and found his dream location in Colorado, where he produced the ideal coverage with Gary, a young cowboy who matched the criteria perfectly.

During this assignment, he also took other photographs for his personal work: one of young Gary’s friends was on the school bus, looking out of the window, just where the glass had been hit. The impact of a stone? A bullet? An accident? Whatever the case, the thought of a violent event creeps into this image, contrasting with the child’s face. Yet there is no staging, no involvement and no dramatic consequences.

The impact automatically catches the eye, leading us to overlook a clever composition structured around strong vertical and horizontal lines framing the child’s face. The natural light highlights four successive planes that create depth: the frame of the bus, the window, the child and the opposite window opening onto the street.

This enigmatic photograph was never chosen by any publisher. Elliott Erwitt would later say that he gave this photograph to his optician, who never displayed it in his shop.

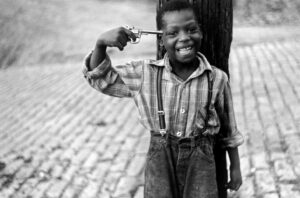

Pittsburgh pistol

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA,

1950

Pittsburgh pistol

In 1950, Roy Stryker, the first client of the young Elliott Erwitt, integrated him into an army of photographers with a mission: to document the industrial transformation of the city of Pittsburgh. Elliott Erwitt spent three months there and returned with dozens of rolls of film. It was a dream assignment that gave the photographers a great deal of freedom. This mission was unfortunately interrupted by his mobilisation with the American army. But what remains is irreplaceable documentary work on urban developments and a totally destabilizing photograph: the one of the little boy pointing a gun at his head. As he walked through the streets of the city, he came across this little boy with a gun. It was a toy. He chatted and played with the child for a while. He took about ten shots of their play time, of which he kept the second photo, this one. Elliott Erwitt says it is one of his favourites: it causes people to either laugh or cry. For him it is the archetype of successful photography. It expresses ambiguity, even contradiction.

EE : “Contradictions are perfect for photographs, they make them interesting.” “I think the most important thing you can do in a photograph or in photography is to evoke emotion, to make people either laugh or cry, or both emotions at the same time.”

French baguette

Provence, France,

1955

French baguette

This photograph, taken at one end of a French main road lined with plane trees, is like a snapshot of a moment in time.

EE : “The picture here was taken for a publicity campaign to bring people to France for the French tourism campaign. It was taken in 1955, in those days advertisements were a lot more or sort of much more interesting than they seem to be now. They were more photographic in the sense of being real and in the sense of being almost journalistic. Things have changed but the picture remains.”

During their stay in France, his travelling companion, the American director of the tourist promotion agency, noticed that he often saw people carrying bread. The idea of using the baguette came to mind, and then the other elements fell into place: their real driver would act as a fake bicycle rider and his own nephew would be the child with the baguette. The staging took some time but Elliott Erwitt found a neat trick.

EE : “You will notice the small stone here, as this picture was set up, and as my camera was set up, I had to be sure to get the picture in focus so the stone indicates the focal point of my camera. Of course I had these people go back and forth a few times to get the right expression on the boy’s face, and to get the right conditions. So whenever the bicycle passed the stone, I would press the trigger of the camera and take the picture. I think I must have done that about a dozen times and then chose the one that was most accurate and… this photograph.”

Here we can see how Erwitt uses his sensitivity to respond to sales orders, turning a simple advertisement into a tribute to the art of living in France.

EE : “They are totally French, the bike and the bread too!”

Dogs and things that are funny

New York City, USA,

2000

Dogs and things that are funny

This shot shows how « funny things are ».

Elliott Erwitt says he took this photograph near his home while walking his own dog. He says that he had already made friends with the human and canine inhabitants of his neighborhood, exchanging dog-walking tips. This is a snapshot: the owner of these large dogs is resting on the steps when one of them sits comfortably on his lap and hides his face. The dog stares into the photographer’s lens. Nothing complicated, just confirmation that it is not necessary to try to be humorous but that « things are funny« .

Competition dogs

Birmingham, England,

1991

Competition dogs

EE : “Last year I came across the Crufts show, just outside Birmingham, there were something like twenty-five thousand dogs, all from the British Isles. Rumours were rife about some illegal practice of dyeing, lacquering, cosmetic surgery. Dog owners exchanged comments such as: « The ideal basset hound should have a calm and cheerful expression ». During the entire exhibition, the dogs act the part”.

He had seen dogs in every country except China, and he pities the Latin American ones who always look unhappy. He finds the American family dog very relaxed.

These are decidedly British dogs: as with the beaches, Elliott Erwitt carefully observes canine and human attitudes and national customs.

EE : “When British people talk about Gladys or Campbell, Rosie or Mister Mudge, you have to listen very carefully to find out if they are talking about their wife, husband, sister, neighbour or one of their dogs. The way they pronounce these names gives you no clue.”

Dogs that jump

Ballycotton, Ireland,

1968

Dogs that jump

EE : “This Yorkshire Terrier defying gravity was not as weightless as it seems. He didn’t jump up and down like that to please me, but because I barked at him.”

The little Yorkshire hanging in the air is Erwitt’s own dog taken by surprise during a walk. Only the separation of the dog from his shadow helps us understand that he was startled.

Elliott Erwitt used to stand behind the dogs and their owners. Then he barked, which most of the time provoked a reaction that made for some very good shots.

EE : “This way, I provoke a reaction worthy of being recorded on film. Dogs don’t usually change their expression, but a sudden noise sometimes triggers a glare or an outraged expression. To catch a unique image, you have to upset their sense of security, make them feel uncomfortable, or else they won’t pay any attention to you.”

It also occasionally happened that the owner reprimands his dog thinking that he’s the one at fault.

Paris, France, 1989

In another photograph, a white dog levitating: perfect framing, alignment of the feet of the man in the raincoat, this is a dog actor and a staged shot that combines two of the photographer’s great passions: hanging dogs and legs.

It is a French dog, who seems to have an unusual character.

EE : “They are aware that they are part of the social fabric. You can see it in their expressions. They also have a strong sense of territory, in a specifically bourgeois way. They know full well that it is their butcher’s shop, their café, their second home, and they will never forget it. I’ve never found French dogs to be particularly friendly; they certainly have no sense of humour.”

Dog shoes

New York City, USA, ca.

1950

Dog shoes

In 1946, Elliott Erwitt was 18 years old. Commissioned by a shoe brand, he took his first photograph of this kind.

EE : “My first dog picture that was published was in 1946… Every now and then I look at my contact sheets to see what was on them, and I ended up noticing that there were a lot of dogs. That’s how the dog thing started. One of the first series on this theme came about as a result of a commission for the Sunday supplement of the New York Times. It was a fashion photo for women’s shoes. I decided to photograph them from the dog’s point of view, since they see more shoes than anyone else. It’s a professional dog, a paid model.”

A dog’s view of the world brings about a revolution in the way we look at things. In this photo and the next one, we note the lively and direct exchange of glances between the photographer and the animal. The dogs and the shoes are in focus, to honour the commercial contract, the background is blurred and artistic. In the second photo, the framing, which excludes the Dane’s hind legs, makes him appear strangely human.

New York City, USA, 1974

EE : “Les chiens professionnels présentent plusieurs avantages. Moins chers que les humains de location, ils sont plus séduisants au sens où chacun d’entre eux a un look bien précis. Les filles qui sont mannequins se ressemblent toutes ; elles sont toutes grandes et maigres. Elles présentent la mode de l’année. Chez les chiens faisant profession de mannequins, je discerne de subtiles différences individuelles. Les tendances de la mode ne les concernent pas”.

Museums, frames, lighting

Le musée du Prado, Madrid, Espagne,

1995

Museums, frames, lighting

Taken at the Prado Museum, this shot is typical of unstaged photographs. Elliott Erwitt positions himself, frames it, and waits for something to happen. Here, the group of visitors has been magically divided: the men are grouped together in front of the nude version of the work, while the only woman is facing the clothed one.

Château de Versailles, France, 1975

In this photograph, there is an amusing overlap between the works of art and the visitors to the room displaying the portraits of academics at Versailles. The portrait of the sculptor François Girardon is looking on, a little distressed, at these curious people contemplating an absent painting and an empty frame. The frame is an essential feature of museums:

EE : “It is extraordinary to see how it is enough to add value to a work that doesn’t always have any. It is often the case that the frames are of greater artistic value than what they enclose. It’s also strange that in many museums, especially in Europe, you can’t see the paintings because of reflections and bad lighting. I just think it’s a funny idea to display things that you can’t see.”

Elliott Erwitt has one rule for the inscriptions on his work: they must be short and contain only the date and place. Sometimes, in the case of well-known personalities, the name is added. In this way, the visitor focuses on the photograph itself and not on the explanation.

EE : “Some visitors spend more time looking at the inscriptions than at the works themselves. Almost everything you see in a museum is the work of a dead or dying artist. So we tend to look at the dates, to think about how old the artist was when he produced this or that work of art, or how old he was when he died.”

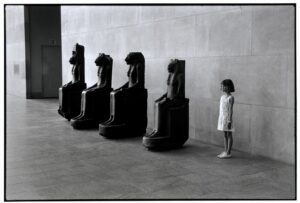

Diana the Huntress

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA,

1954

Diana the Huntress

This is one of the earliest photographs in the exhibition. Taken in 1949 at the Metropolitan Museum, it implies that it is not the visitor who is observing the artwork, but the other way around. This humorous perspective contrasts with the conventional and intimidating appearance of the museum. We can almost hear the resigned visitor’s footsteps receding, echoing in a sacred, museum-like silence.

EE : “I devised a little technique to get around the legislation and successfully take photographs in a museum. All you need is a small camera that is inconspicuous and doesn’t make too much noise. When the attendant is not watching, you adjust it to eye level and cough slightly while pressing the button to disguise the noise of the shutter release. You can also bribe the attendant, a more efficient and direct practice in some countries.”

In those days it probably took more ingenuity than today to take pictures in museums.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA, 1988

USA Rangerettes

Kilgore College Rangerettes, Kilgore, Texas, USA,

1963

USA Rangerettes

In 1964, Paris Match commissioned him to do a feature that would restore the image of Texas, tarnished by the Kennedy assassination in Dallas. The aim was to paint a portrait of Texas, a place that nobody understood. The specifications were to include « big ranches with real cowboys, extravagant houses, oil tycoons, flags and monuments to national heroes ».

Elliott Erwitt spent six days there and brought back eighteen colour rolls and twelve black and white ones. In his working notes, he added what Texas meant to him and what should stand out in his pictures:

EE : “…guns, adolescents attitude, guns, guns; conspicuous; Mexicans; bigness obsession; and ‘solace in wealth’.”

Paris Match finally selected eleven of the most impressive photographs for a feature entitled « Texans, America’s Unloved Ones ». Among them, the Rangerettes as a symbol of Texas corresponded in every way to the expected image. To Erwitt’s disappointment, some of the photos, such as those dealing with the civil rights issue, were not selected.

This story gave him the idea of making a documentary a few years later, Beauty Knows no Pain, about the Rangerette movement and its founder. He observes and portrays on screen the self-sacrifice required of these women and reflects on sacrifice, identity and conformity. His film is a statement of fact, leaving viewers to draw their own conclusions.

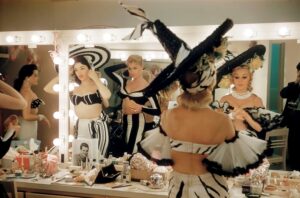

The Americas 50/60

USA, 1950s. Family at lake

1956

The Americas 50/60

From 1950 onwards, Elliott Erwitt lived and worked in New York while developing an in-depth knowledge of the United States. He produced numerous articles in a variety of environments and contexts, for his commissions. During this period, he developed the habit of accepting all offers. Not specialising was one of his strengths.

Thanks to this, he travelled all over the United States: from the fish markets of New York to the cowboys of Colorado, from the cowgirls of Nevada to the portraits of writers, from the transformation of Pittsburgh to the students of an American university, Elliott accepted everything.

We find him photographing the ideal family by a lake, where cars are of great importance, or extravagant situations such as this driver and her tiger, who is, of course, behind the wheel.

In this Nevada hotel in 1957, he shot a series on the show girls of the Las Vegas shows, ready to go on stage, in the exuberance of the dressing rooms. In the following photograph, of contrasting sobriety, we can see the other side of the coin, the same young women at the door of a much less luxurious motel.

Los Angeles, California, USA, 1956

Los Angeles, California, USA, 1956

Tropicana Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 1957

Showgirls, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 1957

Russia, Siberia 60

La Place rouge, Moscou, URSS,

1968

Russia, Siberia 60

Elliott Erwitt returned to the USSR to cover the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. This photograph of Red Square, taken from a simple apartment, bore no resemblance to the images of the 1957 parade in which he showed the world the Soviet missiles. The grey curtain of the window seems to take away what is left of the colour of the setting. Erwitt brilliantly switched between conventional photojournalism and a closer look at the everyday life of Soviet citizens. This time his journey extended to Siberia, where he did an in-depth article that showed a different face of Communism to the simplistic one created by Europeans and Americans.

As everywhere, people go about their business: an appointment with the hairdresser and her steam machine, a visit to the sauna, a dance club or a courageous winter bath in a frozen lake.

Bratsk, Siberia, USSR, 1967

Bratsk, Siberia, USSR, 1967

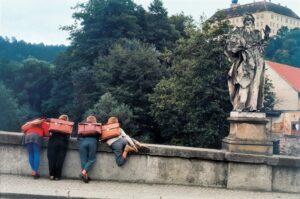

Eastern Europe 64

Częstochowa, Poland,

1964

Eastern Europe 64

In 1964, Life World, which publishes volumes on foreign countries, commissioned Elliott Erwitt to write a feature on Eastern Europe. The aim was to introduce Americans to this unknown world. The criteria were clear: a photographic portrait of daily life in the satellite states of the USSR, to present « an image of these countries, their beauty, their traditions, a measured and realistic vision ».

On a simple tourist visa, to keep a low profile, Elliott Erwitt left London in a hire car and travelled over 5,000 km in three months through Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.He described how the weight of the past resurfaces and how politics was present even if people pretend to ignore it.

EE : “And that was interesting because at the time it was a time to be in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and all those places. And consequently I got some nice pictures because I was really working for myself or for my perceptions rather than for some editor’s preconceptions”.

The success of this assignment was that, while respecting the instructions, it circumvented certain political limitations by masking them under the anonymity of everyday life. He would later say that this mission beyond the Iron Curtain was the most exciting of his career.

Of the 21 photographs selected, the publisher didn’t take the most interesting ones. For example, this series of photographs taken in Poland shows a priest giving confession to the faithful in the middle of the street. The magazine wouldn’t publish the framing you see here, which is the most balanced: Eliott Erwitt shows us the whole confession process in three stages, from the large queue of people chatting, to the confession itself and finally to the penance. A different framing was chosen, showing only the queue on the right and leaving the scene incomplete.

His interest in this part of Europe did not wane. In 1968, he met Josef Koudelka, who became his colleague and friend at Magnum, and helped him to obtain the famous photographs of the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia.

Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1964

Poland, 1964

France 50/60

Saint-Tropez, France,

1959

France 50/60

Erwitt maintained a special relationship with France, where he was born, and Italy, where he grew up. He took every opportunity to return to both.

In the 1950s he began to receive commissions from the travel magazine Holidays. These contracts were for demanding multi-page features but they paid well and allowed him to travel the world.

At the same time, he received commissions from the French tourism promotion agency. For almost ten years and to his great delight, these missions were opportunities for him to travel around France. He knew the country very well, but above all he captured its essence, from the luxury hotels of Paris to the beaches of St Tropez. These advertising campaigns are another example of how he combined his artistic and commercial interests.

Hotel Ritz, Paris, France, 1969

Advertisement for French tourism, Paris, France, 1963

Italy 50/60

Vatican City, Rome, Italy,

1965

Italy 50/60

Elliott Erwitt returned to Italy to work for the tourism promotion agency and to cover events such as the papal elections in the Vatican.

From his Italian childhood, he retained a sensitive and accurate way of photographing this country. The Italian neo-realism movement, initiated by Visconti, influenced his early work and contributed to his love of cinema. These photos of Italy look like something out of a Federico Fellini, Vittorio de Sica or Ettore Scola film. Elliott sums up his relationship with Italy in three words:

EE : « Wonderful, Wonderful, Wonderful”.

Venice, Italy, 1965

Corporate commissions

The 200-inch mirror created for the Hale Reflecting Telescope at Palomar Observatory, Corning, New York, USA,

1976

Commandes corporate

Corporate commissions, often industrial, played a very important role in Elliott Erwitt’s career for two reasons: on the one hand, as we have already seen, he accepted any type of request without limitation and considered any assignment to be an opportunity to experiment and to take a break from his usual subjects. On the other hand, it was during one of his first contracts in the 1950s, for the Standard Oil Company in Pittsburgh, that he realised the absurdity of handing over the rights to his negatives to private companies. The condition of retaining his rights meant that he had to give up some of his assignments.

He worked for companies that made the least inspiring products for an artist: life insurance, chemical by-products, industrial glass and even household appliances and kitchens.

Some of his clients remained loyal over the years, such as the Corning glass, ceramics and optics company. He took this photo of a giant telescope mirror. The child provides the scale, of course, but it symbolises the future, the hope that comes with knowledge. Note the formats of the prints, which are almost square, and that the human element is everywhere, even when well hidden. These photos of commercial projects were often distributed within a professional communication circuit. Featuring them is therefore more unusual.

Allied Chemical facility, New Jersey, USA, 1967

Sam Goody Hi-Fi, New York City, États-Unis, 1955

International trips

Puerto Rico,

1959

International trips

Elliott Erwitt was a tireless traveller. Although the United States and Europe remained his favourite haunts, he travelled the world to discover others. He went on assignment for Holidays, a faithful client, and obtained new commissions, often from the tourist offices of the countries he visited. This was the case with Puerto Rico in 1959, the first of many trips.

His gaze moved quickly beyond the horizon of the beaches to show Americans the authenticity of its inhabitants.

EE : “If photography is an art of observation, it has little to do with the things we see and everything to do with the way we see them.”

Other tourist agencies wanted his perspective.

In 1977, he took the plane again, this time to Asia, still on assignment. He was in Korea, then in Japan, two countries he had known for decades. Although photographers appreciate the Asian sense of aesthetics, in Japan for example, and also the persistence of strong traditions. Without ever changing his method, Elliott Erwitt’s eye captured other ways of being and living, like an ambassador of a poignant humanity.

Kyoto, Japan, 1977

Kyoto, Japan, 1977

Project HBO Japan

Amsterdam, Netherlands,

1982

Project HBO Japan

In 1981, Elliott Erwitt was commissioned by the American Home Box Office to make a documentary entitled Hedonism about the leisure activities of billionaires. It shows absurd leisure activities such as $10,000 hunts or, as shown in the picture, taking a collective bath in Japan, in charming company, for $10 a minute.

This first documentary was so successful that it became a five-part series, The Great Pleasure Hunt. Viewers were treated to an appetizer of caviar and champagne in Paris, followed by poison fish in Amsterdam, then grilled pig in Hawaii, and ending with a flower salad in San Francisco.

But HBO did not stop there. It commissioned him to make 6.5 hours of documentaries about sex in all its forms. He seems to have had a lot of fun while making these films. His documentary adopts no accusatory or denunciatory tone. He reveals what he sees, observes how the protagonists of these pastimes behave and leaves it to the viewer to draw whatever conclusions they wish.

HBO would eventually change its broadcast orientation.

Fashion in the 80s

Fashion shoot, New York City, USA,

1989

Fashion in the 80s

Since the 1950s, Elliott Erwitt had been working for the fashion world as seen with the shoes and dogs at the beginning of his career. It is striking to note that 40 years later, the same recipes of his photographic genius produce the same effects: perfectly mastered staging giving the impression of a natural photograph with an unexpected detail that makes each shot unforgettable. As he was passionate about the world of beauty, he produced a film in 1980 on the hidden side of agencies, Beautiful, Baby, Beautiful.

Here, the series taken in New York plays on the natural aspect of an unreal situation: a model having her shoes shined or another facing an exhibitionist. Even more unreal is the Italian model lifting her car that had broken down. An absurd way of combining the woman and the car, two mobilising themes in advertising.

From the beginning of Elliott Erwitt’s career, technology evolved a lot. Digital technology now offers the possibility of infinitely modifying photographs. As a matter of principle, Elliott never altered his own photographs, at least never his personal work. He allowed himself a margin for publicity shots.

EE : “If you’re selling cornflakes or automobiles I think manipulating is… it’s sort of expected because nobody believes those things anyways. But obviously manipulation is totally unacceptable to me in photography. Photography has to do with what is, not what you manipulate or what you conjure up.”

Fashion shoot, New York City, USA, 1989

Fashion shoot, New York City, USA, 1989

Milan, Italy, 1991

Personalities from the world of Art

American singer/actress Grace Jones and artist Andy Warhol, New York City, USA,

1986

Personalities from the world of Art

This photograph, in an unusual format, features two American celebrities from the 1980s: artist Andy Warhol and model and singer Grace Jones. The photograph is dark, with a few spots of light illuminating the two stars. The staging and the long format of the print are impressive: the back seat seems narrow while the limousine is gigantic. Erwitt’s attitude towards artists, famous or otherwise, is always the same: discretion and humour, even when sometimes you have to wait for them.

EE : “Grace Jones was supposed to be sitting next to him but she was late so I decided to use my daughter instead”.

There is indeed a photograph of Erwitt’s little girl sitting next to a Warhol who is more intimidated than she is.

A few days later, Andy Warhol died following an operation in New York. The very next day, Elliott Erwitt received a call asking for the negatives, as this would be Andy Warhol’s last series of posed photographs.

The Moscow kitchen 1959

Nikita Khrushchev and Richard Nixon, Moscow, USSR,

July 1959

The Moscow kitchen 1959

Sent on a mission by Westinghouse refrigerators to Russia in 1959, Elliott Erwitt, in the middle of reporting on the American trade show in Moscow, took this photo.

EE : “Vice President Nixon at the time came on a state visit, so I joined the press officers. I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time and to be able to take a picture that later became very famous. A little bit because of the two subjects, a little bit because of the Cold War, and a little bit because of Nixon’s and Khrushchev’s arrogance, it had all the right ingredients for the success of that photograph. When they arrived, they practically posed in front of me. This is how a photograph can lie. It gives the impression, but not the substance. This photo helped create the image of Nixon as a strong man against the Soviets during the Cold War. In reality, he was extolling the superiority of red meat…over red cabbage. In photography, luck is extremely important, it is one of the most important factors”.

This photograph, very cropped, was used and above all reproduced in all forms of promotional products for the campaign: stickers, posters, postcards and even badges. It became the campaign poster for Nixon’s presidential campaign and was printed in millions of copies. Elliott Erwitt was never consulted. He sent them an invoice for $500, which was paid to him. At the time, Erwitt, who was so committed to photographers’ rights, decided not to pursue the matter.

Accredited to the White House, Elliott Erwitt followed the accomplishments and gestures of the Presidents in office, including Kennedy’s career, which was brutally interrupted by his assassination in Dallas in 1963.

President John F. Kennedy in the Oval Office, Washington, D.C., USA, 1962

Coffin of John F. Kennedy placed in the East Room, White House, Washington, D.C., USA, November 25th, 1963

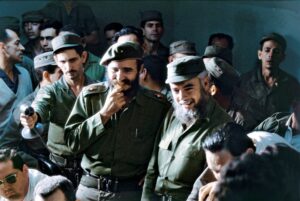

Cuba 1964

Che Guevara, Havana, Cuba,

1964

Pieta

EE : “Taking photos of celebrities isn’t any different from taking those of non-celebrities, except that celebrities sell better”.

In 1964 Elliott Erwitt travelled to Cuba. He was sent by Newsweek magazine but travelled with a group of journalists from the ABC television channel. He was to photograph the Leader Massimo and provide reassuring photographs of daily life in a country that had become dangerous. For one week he was Fidel Castro’s guest and followed him on visits to families, walking around kitchens and village streets, carrying babies in his arms.

He brought back hundreds of photographs, including several exceptional ones. This one is from a series where he appears to be face to face with Che Guevara.

EE : “I can compare him to a cowboy… He was friendly, pleasant, interesting and very photogenic. I would say he was the Marilyn Monroe of that time. He seemed to be in a good mood, as far as I remember. And he even gave me a box of cigars that I couldn’t take to the States because it was prohibited. I was sad about that box of cigars…He was a fine man.”

Henry Louis Gates who prefaces the book on Erwitt and Cuba writes:

« The photographs bringing Fidel and Che together seem to exude self-confidence, opportunity, control and authority as well as a certain charisma in which one might see an appealing physicality. In fact, this duo looks more like movie stars than political leaders. »

Cuba was a highlight and a key location in Erwitt’s career.

Fidel Castro, Havana, Cuba, 1964

Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle, Moscow, USSR,

1966

Charles de Gaulle

Sent to Moscow by a magazine to cover General de Gaulle’s state visit in 1966, Elliott Erwitt took some photographs during the official part of the visit. He took this shot, which was strikingly natural. Even in such a situation, Erwitt lets De Gaulle « be himself », giving the impression of shared intimacy in a very political moment.

At the end of this staged photo session, he returned to the location and recounts how he managed to photograph the informal meeting between the General and the Soviet government. Thanks to his discretion and a lapse in security, he was able to slip into the room and, in a casual manner, take historic photographs of the meeting. Paris Match published one of these images on its cover with the title « Les cinq secrets du voyage » (The five secrets of the visit).

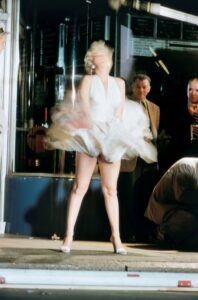

Marylin 1

American actress Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Seven Year Itch, the famous subway grate scene, New York City, USA,

1954

Marylin 1

Elliott Erwitt has always been fascinated by cinema. He found himself on the sets of some of the most iconic films of 1950s America. Magnum negotiated contracts to take the set photographs usually done by the studios. The agency’s photographers were to approach cinema in a different way, taking an interest in other aspects. Thus Erwitt was on the set of Elia Kazan’s On the Water Front, then Billy Wilder’s The 7 Year Itch, then John Huston’s Misfits.

American actress Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Seven Year Itch, the famous subway grate scene, New York City, USA, 1954

This staging in the form of sequenced photographs of several people recalls the now mythical scene in The Seven Year Itch. Elliott Erwitt had the opportunity to meet Marilyn often, forming a warm and sincere relationship with her.

EE : “She was very kind to me, she was an extremely intelligent woman, and we got on well. We had done several sessions with her, and the amazing thing about Marilyn was that it was almost impossible to take a bad picture of her.

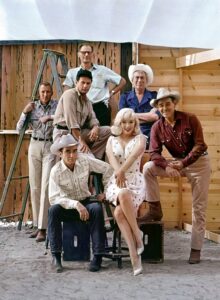

Marylin 2

From left: Frank Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach, Arthur Miller, Marilyn Monroe, John Huston and Clark Gable on the set of The Misfits, Reno, Nevada, USA,

1960

Marylin 2

This carefully staged photograph offers a stunning insight into the world of American cinema, for better or for worse, during the filming of Misfits.

Taken in 1960, it features Frank Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach, Arthur Miller, John Huston and Clark Gable surrounding Marilyn Monroe.

Everything seems to be in place for an artistic climax. However, the filming turned into a form of nightmare, a mythical fall from grace. All the participants were severely tested.

Arthur Miller is said to have written this script for his wife Marilyn, in order to offer her the role she had dreamed of. Their relationship, already very bad, deteriorated. He had her hospitalised twice for questionable reasons. The film was delayed by unforeseen costs. At the end of the shoot, Clark Gable died of a heart attack, Marilyn continued to decline and never finished another film.

EE : “We were Magnum photographers, with ethics, and we never took advantage of these situations.”

Also taken during the film shoot, this portrait is both mysterious and very natural. We sense the discreet presence of the photographer, who, separate from the stressful posed sessions with the actors, captures images on the side that are much more spontaneous and full of meaning.

Marilyn Monroe during the filming of The Misfits, Reno, Nevada, USA, 1960